When Nigeria trembled under the weight of its first military coup in January 1966, one man, a then-young Assistant Superintendent of Police would unwittingly become the bearer of one of the nation’s most tragic revelations.

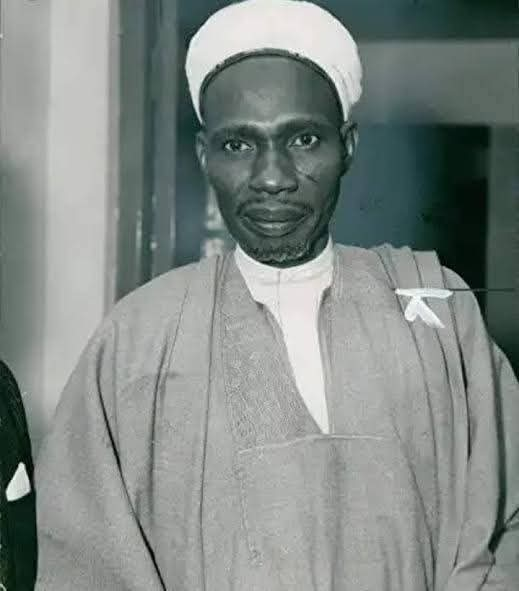

Alhaji Ahmad Ibrahim Babankowa, a native of Ringim (now in Jigawa State), found himself at the centre of history as the man who discovered the decomposing corpse of Nigeria’s Prime Minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa.

Born in 1937 and enlisted into the Nigeria Police Force on February 1, 1960, Babankowa was stationed at Sango-Ota, in the present-day Ogun State, when the winds of insurrection began to blow across Nigeria.

The Western Region had erupted into chaos: ‘Operation Wetie’, a wave of political violence involving arson and mob killings gripped Ibadan, Owo, and Lagos and other parts of the Western region.

To restore order, Babankowa, commanding a special anti-riot mobile police unit, was redeployed from Mubi in the North to the flashpoints in the West.

From his base at Sango-Ota, he led daily patrols through Somolu, Ikorodu, Abeokuta, Sagamu, and Ibadan due to the daily outbreak of violence around the region.

But nothing could have prepared him for the night of Friday, January 14, 1966, when history passed silently before him.

That night, while manning a checkpoint on the Lagos–Abeokuta highway, Babankowa and his men observed a convoy of military vehicles – trucks, a Land Rover, and two Peugeot saloon cars heading toward Abeokuta.

There was no reason to suspect anything sinister; after all, Nigeria was under a state of emergency, and military movements were common during riot control. They were presumed to be on a complementary patrol to restore order.

But inside those vehicles were some of Nigeria’s highest-ranking political and military figures, abducted as part of a coordinated military mutiny.

Among them: Prime Minister Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, Finance Minister Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh, Lt. Colonel Kur Mohammed (acting Chief of Staff, Army HQ), and Lt. Colonel Abogo Largema (Commander of the First Battalion, Ibadan).

The soldiers, Babankowa would later learn, drove a short distance past the checkpoint before diverting into a forest where they executed their captives in cold blood. An hour later, the convoy returned in the opposite direction.

Babankowa and his men, unaware of what had transpired, assumed it was a routine military movement.

It wasn’t until four days later that the true horror revealed itself.

On January 18, 1966, four days after the coup, Babankowa visited the only clinic in Sango-Ota then for treatment when he overheard Yoruba-speaking women complaining about an unbearable stench coming from a part of the bush near the Abeokuta highway.

The women had no idea what it was, only that it had persisted for days.

His instincts stirred. He divided his anti-riot team into two patrol groups and launched a coordinated sweep of the area. Deep in the forest, under the cover of trees, they stumbled upon the horrific remains.

There, crumpled beneath a tree, lay the decomposing body of Prime Minister Balewa, dressed in a now-discoloured white guinea brocade gown, his Zanna cap lying by his side.

His body had swelled from decomposition, and worms writhed beneath the fabric. Nearby lay the corpses of Chief Okotie-Eboh, Kur Mohammed, Abogo Largema, and at least two other victims of the coup.

Unlike other prominent victims such as Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto, and Samuel Akintola, the Premier of Western Region who were executed at their residences, Balewa had been abducted and transported far into the bush before being murdered.

Some historians believe this unusual treatment of the Prime Minister may have been an attempt to extract a confession, delay his execution, or shield his death from public view.

Babankowa immediately reported the discovery to police headquarters in Ikeja, with the help of Alhaji Kafaru Tinubu, the officer in charge.

The acting Inspector General, Alhaji Kam Salem, instructed him to come to Lagos immediately, sirens blazing.

By the time Babankowa arrived at Moloney Street Police Headquarters, General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi had already seized control as Nigeria’s first military Head of State.

Babankowa was disarmed by the military personnel, stripped of his boots, belt, and cap, and marched barefoot into the office where Ironsi sat beside the IG.

Ironsi, speaking in Hausa, asked,

“Ka ce ka ga gawar Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa da ta wasu mutane?” meaning “You said you saw the corpse of the Prime Minister and others?”

Babankowa confirmed. When asked how he could identify Balewa, he explained that he had previously served as a security officer to the Sardauna of Sokoto, and knew Balewa personally.

Ironsi ordered his temporary detention, first planned for the Naval Base in Apapa, but Kam Salem intervened saying:

“If you wouldn’t mind we can put him in detention here in our own custody and produce him at any hour you want him.’‘

General Ironsi accepted the IG’s plea and he was kept him in police custody at Yaba Station.

That night, Prime Minister Balewa’s ADC, Mr. Kaftan, along with the Madaki of Bauchi, an in-law to the Prime Minister, and a military team arrived in Sango-Ota with an ambulance and coffins. Babankowa led them back to the scene. He recalled:

“As a result of advanced decomposition, numerous worms were coming out of his body. We rolled over a white cloth, and had to put my weight on his knee to straighten it to get a perfect position. We attended to the prime minister’s body first before others, and I marked his coffin with an Arabic inscription to avoid a mix-up.”

The bodies were taken to Ikeja Airport, and the Prime Minister’s remains were placed in the baggage compartment of a waiting aircraft conveying his family to Bauchi.

Due to the state of the corpses, no traditional Islamic washing could be performed on Balewa’s body. Instead, water was sprayed and final prayers offered.

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, who once addressed the world at the United Nations as the voice of a newly independent Africa and had been knighted by Queen Elizabeth II as a Commander of the British Empire, was laid to rest with little fanfare far from the pomp and dignity befitting a national leader

Reflecting on those events, Babankowa said:

“If I had known those trucks carried our leaders to their death, I would have intervened. We were 53 heavily armed mobile policemen at the checkpoint. We would have simply overwhelmed them.

They might kill some of us but we would have killed all of them, while those who might have survived the shoot out would have lived to tell the story.

I would have probably been a dead man by now. I would have saved them because I would have launched an attack.”

At the time, a military coup was unimaginable in Nigeria. The country had never experienced one. And so, in that fateful moment, no alarm bells rang.

Years later after the horrific incident, controversy arose. In a 2002 interview, Matthew Mbu, a former minister and diplomat, claimed that Balewa died of an asthma attack, not execution. The claim stunned many especially Babankowa.

“Is Matthew Mbu a medical doctor to certify the cause of death?” He asked

“I discovered them and guarded them until they were finally evacuated for burial. The other people who can lay claim to have seen the corpses were those patriotic officer that I went there with and the Madaki of Bauchi, Maitama Sule, Mr Tapgun, the ADC to the late Prime Minister, and a few military doctors who accompanied us with the coffin.”

“If the Prime Minister died of asthma as he erroneously reported, would he have been possible for him to give up the ghost in the bush with a cabinet member and some military officers on the eve of the first military coup?.

The argument is not logical, it’s sheer rubbish for anyone of sound intellect to get involved in a pedestrian argument bereft of sound reasoning. Matthew Mbu doesn’t know anything about the issue he has raised.”

“There was no official autopsy, and the body was too decomposed to determine exact cause of death. But to those who discovered the scene, execution was undeniable.”

To Babankowa, the spread of such revisionist claims was not innocent, it was part of an orchestrated agenda to distort the historical truth and bury the real causes of Nigeria’s first national tragedy.

The January 15, 1966 coup, led by Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna, and others, was Nigeria’s first. Though publicly framed as an attempt to end corruption and misrule but the ethnic pattern of those assassinated, almost all Northern and Western leaders, led to suspicion, outrage, and eventual reprisal.

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa’s murder, along with the killings of Sir Ahmadu Bello, Chief Akintola, and top military officers like Brigadier Zakariya Maimalari, ignited grief and fury in the North.

That fury would explode in July 1966, when a counter-coup swept away Ironsi and brought Lt. Colonel Yakubu Gowon to power plunging Nigeria toward the Biafran War just months later.

The forest at Ota where Balewa fell marked not just a crime scene, but the burial ground of Nigeria’s First Republic.

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa may have died in the forest, but his ghost lingers in the nation’s conscience. In his last national broadcast on January 14, 1966, just hours before he was taken, he said:

“It is important that we should not abandon the path which we have deliberately chosen… the unity of Nigeria.”

And yet, hours later, that unity lay bleeding under a tree in Ota.

As new generations emerge, truth-tellers like Babankowa ensure that the real story of Nigeria’s fall from innocence is never lost.

Babankowa retired as a Police Commissioner in 1984 and lived quietly in Kano he died death in 2015

Katsina Post